In 2014, 17.4 million US households were food insecure[1] — that’s 14 percent of households with limited or uncertain access to adequate food. Meanwhile, seven out of 10 deaths annually (and 86% of health care costs) are the result of chronic disease.[2] A growing body of literature illustrates how food insecurity perpetuates a cycle of poor chronic disease management and increased spending on health care. The effects are particularly acute in older Americans.

TACKLING HUNGER seeks to find and disseminate effective strategies to address food insecurity and its relationship to acute medical events in people with chronic diseases. Through cutting edge, actionable research, we intend to drive public policy change and program innovation at the federal, state, community, and institutional levels. The project focused on adults aged 50 and older with chronic disease who experience food insecurity. The project was built around three components: The Tools for Change toolbox, the Economic Burden Study, and the Exploratory Evaluation.

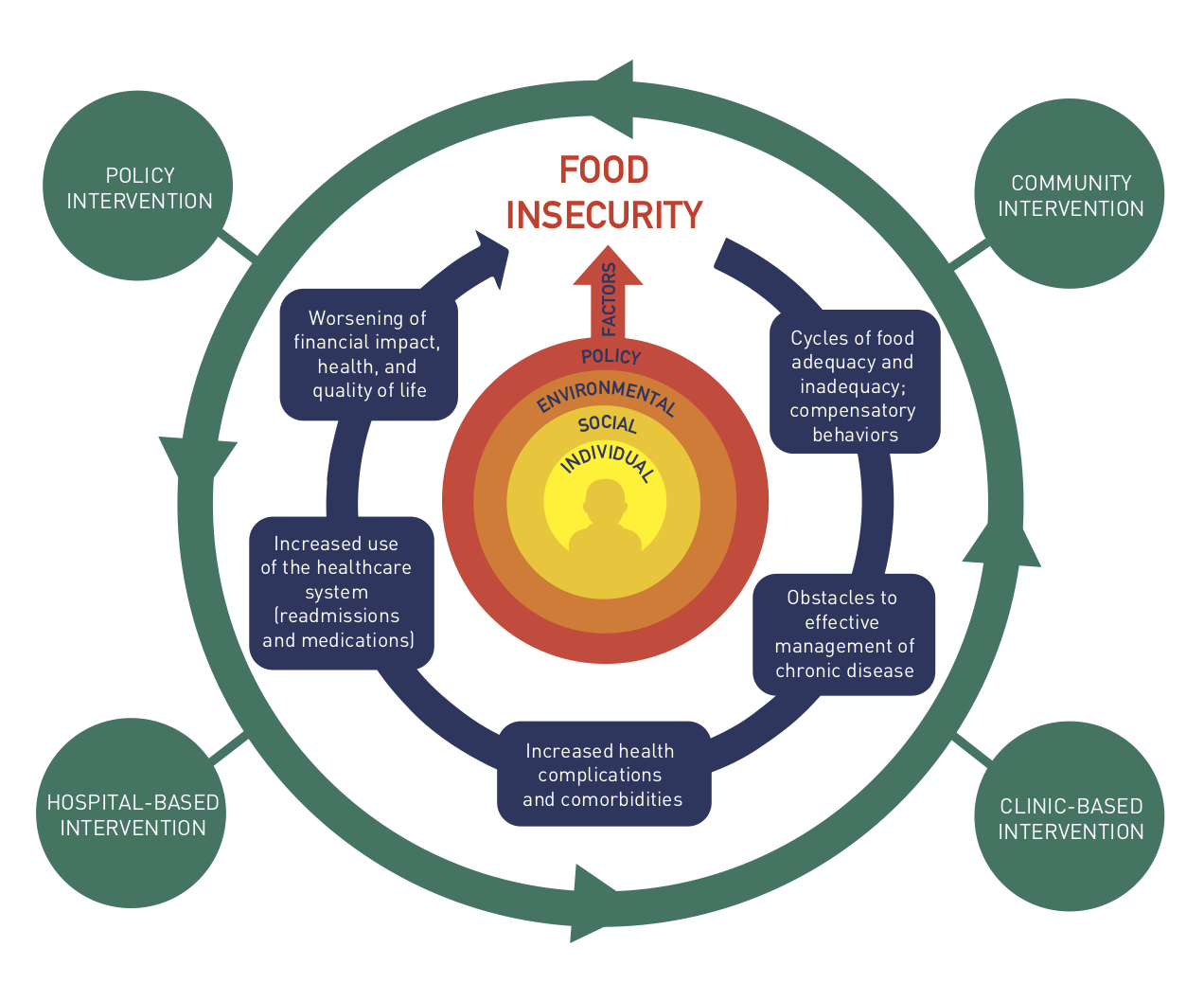

Reversing the Cycle of Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease in Older Americans

This conceptual framework was developed by the Tackling Hunger project as a visual overview of the negative cycle of impacts that food insecurity has on health, and the types of interventions that have the potential to reverse the cycle. Intervention intensity and dose should be considered to maximize the impact of individual interventions; alignment across interventions in a manner that is mutually reinforcing will enhance potential for reversing the cycle. The Tackling Hunger project examines components of the cycle and interventions that aim to reverse it, and offers proposals for improving health outcomes through integrated community, health care, and policy solutions.

The framework was adapted from a similar model developed by Hilary Seligman and Feeding America

TOOLS FOR CHANGE

TACKLING HUNGER has developed a set of tools, including policy briefs and guidance on Community Health Needs Assessments, designed for program practitioners, advocates, and health system leadership. The tools are meant to raise awareness of the complex issues surrounding food insecurity, chronic, disease, and health care costs and to disseminate information on programs that seek to address these problems. They can be used to inform discussions with health system leadership and policy makers on the importance and effectiveness investments that address food insecurity.

Making Food Systems Part of Your Community Health Needs Assessment is a practical guide to assessing local food systems and food security as part of the community health needs assessments that are conducted every three years by nonprofit hospitals. It provides links to user-friendly tools and strategies. The guide points to existing online sources of baseline data and metrics and case examples of collaborative partnerships between hospitals and food system stakeholders. It includes examples from food policy councils, food banks and pantries, and public health departments across the country. The guide is designed to support a local dialogue that encourages stakeholders to share experiences and identify existing tools, data, and resources. This process will create synergistic linkages and an ethic of shared ownership of the community’s health and well-being. Download Guide

Addressing Food Insecurity in Older Adults: Health and Health Care Costs provides much requested information describing the economic impact of food insecurity on health care costs. The brief emphasizes the impact on older adults. It concludes with a short description of policies and programs designed to alleviate food insecurity. Food security advocates and others addressing social factors that impact health can use this brief as a tool in discussion with both health system leadership and local, state, and federal policymakers. Download Policy Brief

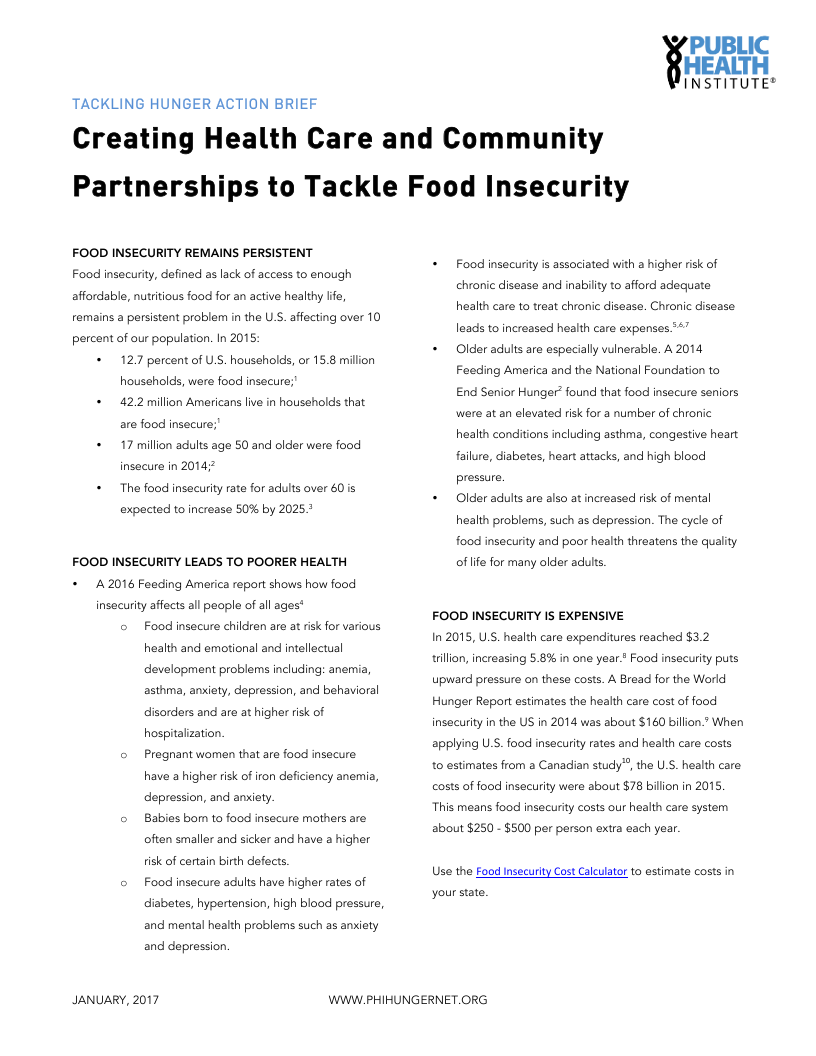

Creating Health Care and Community Partnerships to Tackle Food Insecurity is a resource for community organizers aiming to address food insecurity in partnership with health care organizations. The Action Brief provides facts about food insecurity and its negative health and economic consequences, and outlines examples of ways in which community and health care organizations are partnering to address food insecurity across the country. The brief concludes with actionable strategies for getting started in building health care and community partnerships, and addressing food insecurity, in your community. Download Action Brief

Evaluation Resources

Evaluation is a critical component of any program – to identify areas for improvement, demonstrate program success to potential funders, and build the practice-based evidence to support the field. Newly launched programs should consider establishing baseline metrics and data collection protocols at the development stage, to assist with future evaluation efforts. Programs that are already underway can use predictive analytics and rapid cycle evaluation to improve program effectiveness. Below, we have compiled a sampling of evaluation resources that may be beneficial to program practitioners and health care leaders when implementing food insecurity programs.

When developing an evaluation plan, consider how to achieve maximum results while placing a minimum burden on program participants. Evaluations should include both short-term and long-term outcomes to measure early success, identify areas for improvement, and track progress toward long-term goals.

CDC’s Program Performance and Evaluation Office offers information and resources for public health evaluation:

Community Tool Box is a user-friendly toolbox adapted from CDC’s resources from the Work Group for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas

The National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR) offers resources for health care-community partnerships that address obesity prevention, many of which are adaptable to the food insecurity context. Resources include a sample logic model for that programs may consider adapting as part of their evaluation efforts:

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality issued a paper on “Using Rapid-Cycle Research to Reach Goals, Awareness, Adaptation, Acceleration.” This report will be particularly useful for programs that want to quickly assess components of their intervention for continuous quality improvement and evaluation purposes.

Economic Burden Study

Food insecurity in older adults with chronic diseases is a critical public health concern and an expensive problem.

When people have uncertain access to food, their health and quality of life suffer. In fact, food insecurity has been associated with obesity, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, asthma, and depression. Food insecurity in the U.S. is a concerning and expensive problem. But how much does it really cost us?

A Bread for the World Hunger Report estimated that in 2014 the health care cost of food insecurity was $160 billion.[i] Using information from a Canadian study [iii], our national food insecurity rate, and U.S. health care costs we estimated that food insecurity cost us $78 billion. This means that food insecurity costs our health care system $250 - $500 per person.

TACKLING HUNGER used these numbers in its Food Insecurity State Cost Calculator to estimate the cost of food security in each state. We applied the 2015 USDA state food insecurity rates [iii] and adjusted state costs for regional variations. Check out the costs in your state. Then do something about it!

Incremental Health Care Costs Associated With Food Insecurity and Chronic Conditions Among Older Adults studies health care costs as related to food insecurity — the inability to access sufficient and nutritious food for an active, healthy life — which has been identified as a critical social factor that carries negative nutritional, physical, and psychological health implications for adults. More than 29 million adults experienced food insecurity in 2015. Over the past 2 decades, the prevalence of food insecurity in US households remained above 10%. Research suggests that from 2005 through 2025 the food insecurity rate will increase by 75% for adults aged 60 or older.

There is increasing evidence that food insecurity is associated with chronic health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, asthma, arthritis, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema. Download Study

Explore costs state by state using the U.S. Food Insecurity Healthcare Costs tool via public.tableau.com. Explore potential impacts of changing costs using the U.S. Food Insecurity Cost Estimator also via public.tableau.com.

[i] Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services. National Health Expenditures 2015 Highlights. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf

[ii] Cook JT, Poblacion AP. Appendix 2: Estimating the Health-Related Costs of Food Insecurity and Hunger. In 2016 Hunger Report. Bread for the World. 2016. http://www.hungerreport.org

[iii] Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, Dachner N, Gundersen C, Kurdyak P. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2015;187(14):E429-E36.

Exploratory Evaluation

Hospitals, health care systems, and clinics across the country are working to identify and address food insecurity in patients with chronic disease.

A growing number of health care systems have begun to address social factors that affect health, including food insecurity, in their patient populations. Health care reimbursement models have also shifted toward value-based reimbursement, further pushing health care toward upstream preventative care models. As health care providers take on a new role, launching innovative programs to address social factors, and develop clinical-community partnership models, there is a critical need to assess these health care driven food insecurity programs. Identifying best practices that are scalable and replicable enables government agencies and private foundations to invest their funding streams into proven strategies that will return proven outcomes. Establishing an evidence base of best practices also allows program practitioners who are often working with the limited resources of funding and staff time to invest in strategies that are proven effective.

Toward these goals, TACKLING HUNGER has conducted the first phase of an exploratory evaluation to identify and assess promising practices in health care to address food insecurity and improve the health of patients with chronic disease. The exploratory evaluation used the Systematic Screening and Assessment (SSA)[1], a proven method used by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and others to expand practice-based evidence and conduct efficient, cost-effective, pre-evaluations of emerging innovations to identify promising practices and provide real time feedback to the field. The SSA method is used to identify a wide range of programs through a nomination solicitation process, allowing researchers to identify new and emerging programs, and engages an expert Consultative Group.

Exploratory Evaluation of Food Insecurity Programs Initiated by Health Care Organizations: A Summary Report of Tackling Hunger Consultative Group Recommendations shares our findings from the first phase of the exploratory evaluation, describing the methods that we used and the recommendations of the Tackling Hunger Consultative Group (CG). The comprised a panel of experts who reviewed a selected set of programs, determined which were appropriate for the next step of the exploratory evaluation, and made recommendations in general for the development and evaluation of this growing field. The findings and recommendations provided in this report will guide the next steps of the Tackling Hunger Project. Download Report

Evaluation Resources

In conducting the exploratory evaluation, we identified the need for evaluation support for health care initiated food insecurity programs. Many program implementers themselves expressed interest in evaluation resources, a need that was echoed in the CG recommendations. As a preliminary step, we have compiled useful evaluation resources in the Tools for Change section of this page, above.

[1] Tackling Hunger followed the SSA methodology described in: Leviton, L.C., Kettel Khan, L., & Dawkins, N. (Eds.). (2010). The Systematic Screening and Assessment Method: Finding Innovations Worth Evaluating. New Directions in Evaluation, 125.

[2] We use the geographic regions as defined by the United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service:

Learn more about the TACKLING HUNGER team and partners here.